Home > Bart Beaty's Conversational Euro-Comics

Home > Bart Beaty's Conversational Euro-Comics Conversational Euro-Comics: Bart Beaty On Recent Work From Lewis Trondheim

posted June 2, 2011

Conversational Euro-Comics: Bart Beaty On Recent Work From Lewis Trondheim

posted June 2, 2011

By Bart Beaty

By Bart Beaty

The recent

events unfolding around L'Association has had me thinking a lot about the career trajectories of that publishing house's original founders.

Lewis Trondheim has been the most commercially successful of those seven creators (by far), and he has been recognized with critical praise and recognition from his peers. There was a time not long ago when I would have argued that he was the most important comics creator to have emerged in the 1990s, but in recent years I found myself reading less of his work. Partly this was a function of the fact that he had been so extremely prolific that it was easy to burn out on him, and partly I had a sense that many of his collaborative works with other creators were less engaging than the books he created himself (

Donjon was a notable exception in this regard). A friend cemented this idea for me when he suggested, in an offhand manner, that he never read books that Trondheim wrote but did not draw, because "If Lewis thought it was a good script, he'd have drawn it himself."

That had some ring of truth to it, but this week I wondered if it was fair. So I turned my attention to two of his relatively recent books, one that he drew himself and one drawn by his frequent collaborator,

Fabrice Parme.

Top Ouf

Top Ouf (Dargaud, 2010) is the fourth book in the

Formidables aventures sans Lapinot series.

Lapinot was Trondheim's signature character until he ended that series in 2004.

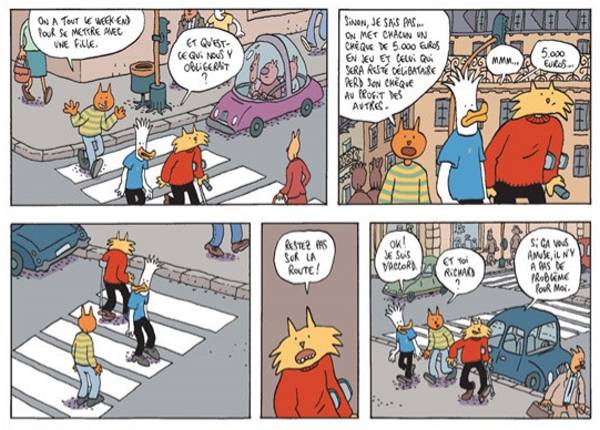

Top Ouf is set in the same fictional universe and shares some of the same characters and continuity, but is missing Lapinot himself. The book revolves around a weekend shared by four loser bachelors -- videogame addicts and germaphobes who each bet 5000 Euros that they can land a girlfriend by Monday. The plot departs from this standard set-up when Richard, Lapinot's good friend, is inexplicably granted the power to make people fall deeply in love with him when he touches them. Over the course of the book Richard never realizes that he has this power -- or that it goes away when he touches them again. Instead he wanders through a fictionalized Paris, becoming a viral video sensation at a tony nightclub and nearly igniting a nuclear conflagration when he meets the President of the United States.

I have to say, I loved

Top Ouf. It wasn't as strong as the best of the Lapinot books, but it was close enough to make me sad that there will probably never be another installment in that landmark series. Trondheim's canny manipulation of genre expectations and off-kilter timing remind me of the zanier

films of the Coen Brothers. The art is consistent but not flashy. Each of the 48 pages uses the same four-tier layout, and the vast majority of his images depict his characters in mid- or long-shot. The effect is televisual in many ways, which seems appropriate for a series that has always had certain

Seinfeldian overtones.

The art in

Panique en Atlantique (Dupuis, 2010) is quite different. This story, the sixth book in the

Le Spirou de... series that invites well-known creators to delve into the universe of

Spirou and

Fantasio, has a '60s aesthetic that is provided by Parme. In the simplest terms: I loved the art in this book. Adored it. Want to roll around in it. Parme channels a '60s animation look so convincingly that the book seems almost completely out of time and place. This is a very different Spirou from that of Andre

Franquin, but it is a cover version of which he might have been proud.

Trondheim previously published an homage to Franquin's Spirou (

L'Accelerateur Atomique, 2003), the last of the Lapinot books, so we've seen what he can do with the character. While I enjoyed

Accelerateur very much, the addition of Parme sends this book to a much higher level, even though the story is slighter and more straightforward than

Top Ouf. The visual style carries so much weight here, that it overcomes some of the shortcomings in what is a very atypical Spirou plot (laid off by Moustic Hotel, Spirou finds himself working on a cruise ship that is then trapped in a protective bubble at the bottom of the sea...). The style, the look, and the tone are all pitch perfect here, even if the story plays out in a way that never really veers from what we expect of it.

Sadly, I would guess that we are not likely to see either of these books in English translation anytime soon.

Fantagraphics' efforts with Lapinot (translations of the second and fourth books) did not meet with great success, although it is possible that their publication of his brilliant early autobiographical comics,

Approximate Continuum Comics, might re-ignite some interest in his work from this period.

Panique en Atlantique is so dependent on a knowledge of other Spirou comics, none of which have ever fared well in America, that it might remain buried beneath the Atlantic like the cruise ship. Alas, for if these books demonstrate anything it is that the master still has plenty of talent to go around.

*****

*****

To learn more about Dr. Beaty, or to contact him,

try here.

Those interested in buying comics talked about in Bart Beaty's articles might try

here.

*****

*****